But if the winds were rough, at least they blew in the right direction, pushing me faster and faster toward Hiva Oa in the Marquesas in French Polynesia.

An hour past dawn on the fourth day of the gale, just where it was supposed to be, Hiva Oa, a 3,000-foot mountain, rose from the ocean. Skinny, long-necked black birds swooped down from its ragged, saw-toothed gray ridges. No medieval fortress was ever gloomier, and you could see why the natives here were once known for cannibalism. But that wasn't what I was thinking about as I fell into the lee of the island and started toward the harbor. I was thinking about my engine. It wouldn't start. Sailing, rather than motoring, into a small and crowded anchorage is like parallel parking uphill in a car with no brakes.

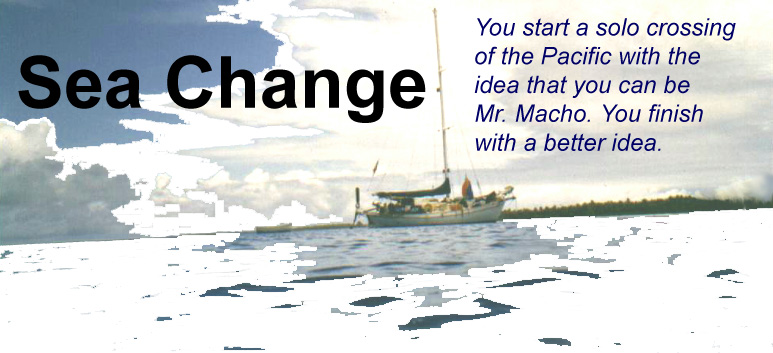

But, hey, said I, you just sailed 3,500 miles alone across a big ocean in a small boat. You can do anything.

And I could have, too, if the cliffs guarding the harbor entrance hadn't swallowed the wind. Had I been better rested, had my wits about me, I might have sensed the vanishing wind moments earlier, turned and escaped. But I didn't. Instead I found myself drifting onto the rocks where waves thundered into white foam.

"This just can't end this way," I kept saying stupidly. Five years of planning and scrimping and day-dreaming simply cannot end smashed on the rocks of my first landfall in paradise.

I

threw down an anchor, and it stopped me 100 yards shorts of the rocks.

But how long in that open, unprotected anchorage would it be before I

was on the rocks, a pulverized pile of fiberglass?

OK, hotshot single-hander. OK, Mr. Macho know-it-all. What are you going

to do now? How are you going to get yourself out of this?

I

am hard pressed to

tell you when I first started dreaming about sailing off alone into the

sunset. A long time ago. One other marriage, four other towns, five other

jobs ago. The dream was like an infection, and once it started growing

there was no killing it.

Many who take to the sea in this way are driven by motives so gloomy I

hate to write about them: antisocial types with hostilities even they

can't clearly define. People fleeing unfortunate alimony settlements.

People fleeing from their consciences and fleeing from the IRS (thank

you, Jimmy Buffet).

I'm not one of those. I offer you a model of social adjustment, a perfectly

healthy, fully integrated, well-adjusted, certifiably normal human being.

I'm happily married (she and my son are flying down to join me), and I

liked my job. (I will say there were days when being associate news director

at the San Francisco TV station with the smallest news audience was not

one unending laugh. But it was fun nine days out of 10, and how many people

can say that about their jobs?)

No, I wasn't lighting out for the territories because I was unhappy where

I was. It was something else. I was fleeing the dreary prospect of a tombstone

reading, "Here lies Robert Hodierne. He never missed a day of work."

A million

times, people asked my why I hoped to sail solo across the Pacific. For

the first

few years I quoted George Mallory and said simply, "Because it's there."

When I got tired of that, I started telling people, "Look, when I'm 90

years old sitting in my rocking chair on the front porch of some retirement

home, I want to be able to say, 'I once sailed a small boat across a big

ocean by myself.'" Let's see the other old codgers top that one.

But neither answer was complete. (Though I must admit that old Mallory

was probably onto something. Anyone who has to ask why you'd want to be

the first man to climb the tallest mountain in the world is not going

to understand any answer, so give him short rations and move on.)

This is a search for adventure in an era short on adventure, even, it

seems, an era intentionally made hard on adventure. This is a time, after

all, when we are so protected from ourselves that even the prosaic step

ladder contains warnings so obvious that only a moron could benefit from

them.

And

not just any adventure will do. Our lives have become such cooperative

ventures that it's hard anymore to point to any one thing and say, "I

accomplished that. Alone, unassisted." Not since I was a war photographer

in Vietnam have I had the unadulterated pleasure of individual accomplishment.

Or the excitement of risk that cannot be shared. ("OK, it's agreed; we'll

share this: You'll be half dead; I'll be half dead.")

Since then there has always been the taint of others: He got good editing;

his assistant did most of the work. I wanted an adventure that would be

mine alone. This is an ego trip.

![]()

All

adventures carry

a price. And the price of this one goes well

beyond the cost of the boat.

My wife, Lisa, and I started paying the price from the time we moved from

the dreaming to planning stage almost five years ago.

Part of the price is the forfeiture of things. Being one of those who

came of age after John Kennedy and before Richard Nixon there was a part

of me that believed an emotional attachment to things was unacceptably

bourgeois. It should therefore be easy to strip things away. And yet …

Years ago, when I was just starting up a life after Vietnam, I had no

furniture and little money. I built my own sofa. It was a sturdy, durable

piece of furniture whose chief (perhaps only) charm was that I'd made

it myself. I sold it and felt a moment of disloyalty to that earlier me.

Like many urban dwellers, my home had once been burglarized. The thief

took the Nikons and Leicas that for 2 1/2 years I had lugged through the

rice paddies and highlands of Vietnam, cameras to which I had a vast,

illogical emotional attachment. With the insurance money from those cameras

I'd splurged impulsively on an extravagant stereo. I sold the stereo and

felt again the loss of the cameras.

And the books. About 800 of them. I don't think I'd ever sold, thrown

away or given away any book I'd ever owned. I had books I'd never read,

nor ever planned to read. I had books I'd read but never planned to read

again. I had books in languages I can't read. It was as if mere possession

of these books meant I possessed their knowledge. It was comforting to

know that Camus was there if ever I was ready to risk that trough, that

Hesse was there in German to humble me, and that Thucydides was there

to settle any dinner arguments that might come up about the Peloponnesian

wars.

I sold what I could, tried to palm off others on my friends and ended

up giving most of them to the Salvation Army. The rest of my things went

out the door without a whimper: prints, bedroom suite, kitchen appliances.

Things. It hardly hurt at all. There was in fact something giddy about

stripping down to essentials, I thought at the time.

What folly. No one buying a boat has stripped down to essentials. He has

traded one set of things for another. There is probably no other hobby

where there are more things to buy. Gadgets abound.

The biggest gadget of all is the boat itself. And buying a boat, especially

your first boat, is a daunting experience. Just as in buying a house,

most people deal with brokers. On a morality scale I'd say boat brokers

rank above TV evangelists, dope peddlers and pornographers, but there

are those who would argue the point. Let's not quibble.

Our boat hunt began early one winter. An especially wet winter. Lisa and

I spent every weekend that season sloshing through sodden boat yards and

marinas, in and out of boats. A scene that repeated itself time and again:

Lisa and I standing on some rickety dock, cold rain streaming down our

faces, our shoes soaked, looking at some derelict boat that we're assured

needs only a little cosmetic work to be able to withstand the worst hurricane.

"Hey, it's best to look at these in the rain," the brokers inevitably

said. "Then you know if it leaks."

We found the boat we wanted. And eventually we bought it. But it wasn't

easy. The low point of the whole episode found me on the phone to the

owner who had failed to show up for the closing. It was a problem with

brokers, he explained. I was so mad that in the middle of my newsroom,

phone jammed in my ear, I rose to my feet, screamed at the poor man at

the top of my lungs and, to the applause of my transfixed colleagues,

slammed the phone down.

Ah, yes, life was getting simpler and calmer already; and we didn't have

the boat yet. The happy ending in my tale is that the brokers ended up

in court at each other's throats like a pack of pariah dogs fighting over

table scraps.

I'll skip lightly over the next few years, though

they were important to me. I left newspapers, went into television, had

a son and consumed endless yellow legal pads figuring out the date at

which we'd finally have enough money to quit and leave.

Shortly before last Thanksgiving I went to my boss and gave a month's

notice. He was, like many of my friends, incredulous. Not many people

quit well-paying jobs three weeks after the birth of their first child.

When my wife's maternity leave was up, she quit, too. Gone were steady

income, health insurance and pension plans.

Gone, too, was identity. One day shortly after I quit, I was making a

small purchase with my MasterCard. Casually, as he was about to ring up

the purchase, the clerk asked, "What do you do?"

It caught me off guard. No one had asked that. Indeed, what the hell was

I now? "I'm a journalist," I finally said, wanting to avoid a long explanation.

"Oh, yeah?" He brightened. "Where do you work?"

"Well, I'm not working right now," I explained briefly. The clerk smiled a brittle little smile and called to check my credit limit.

![]()

Remarkable things

start happening in a marina when you begin outfitting for a serious cruise.

People you've never met stop by to talk, offer advice and help. In a way

you become a celebrity, one who is actually going to live the dreams of

almost everyone who has ever owned a sailboat.

Friends who don't own sailboats get caught up in the same spirit. Our

downstairs neighbor, a graphic artist named Emily Parker, gave up two

days of her Memorial Day weekend to repaint the name on our boat. In-laws

helped pack the boat (no inconsiderable task, I might add), took care

of our son and loaned us their truck.

For a single-handed passage I was getting an awful lot of help.

One of the most remarkable bits of generosity came

from the son of the man whose boat had been tied up next to mine at the

marina for four years, a man I barely knew.

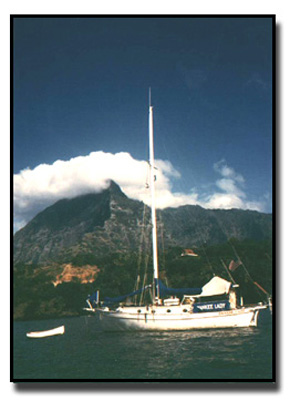

Paul Mazza is the kind of person you meet cruising and is one of the best

reasons to go cruising. Paul has cruised and raced, and he was quick to

notice the gear that was starting to sprout on Yankee Lady -- gear

no one who's going to putt around the Bay needs.

One day, when the boat was awash with supplies, Paul overheard Lisa and

me; we couldn't find the fishing tackle. He gave us his. He heard us on

the phone trying to find someplace that sold canned bacon. He found a

place (and bought us a pound to try).

I told him I couldn't find a solar still for turning salt water into fresh

in case we ever had to abandon ship and go to the life raft. "You know,

I think I have one of those in my truck," he said. I thought he was kidding.

He wasn't. And he wouldn't accept a dime for it. (I'd have paid a marine

store $50 for one.)

"What kind of medical supplies do you have?" he asked one afternoon.

I launched into a practiced five-minute monologue about what a hypochondriac

Lisa is and how we were better stocked than most corner drug stores. He

listened and then asked, "Have a catheter kit?"

"Ah, no, I don't think we do as a matter of fact," I answered.

"You get stopped up out there and it could kill you," he said. He handed

me a sealed, white plastic box. A catheter kit.

Now I have a hard time imagining catheterizing myself in the relative

comfort of my shoreside bathroom. I tried imagining doing it on a moving

boat in the middle of the ocean and I blanched.

What on earth was I getting into?

![]()

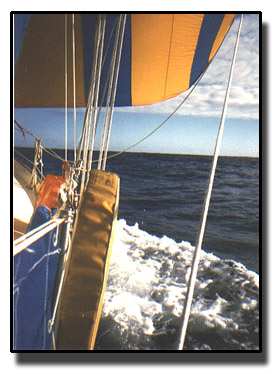

For the first week

I measured my progress away from San Francisco by the clothes I took off.

After day three I wore the sweater only at night. By day seven I took

off the thermal underwear. And by the second week I wore nothing but shorts.

I had found the tropics.

By then my days had settled into a peaceful routine. Up at daylight, increase

the sails, figure out where I was and then slip into a kind of lethargy

that caused one day to blur into another. A long ocean passage, if a sailor

is lucky, is a vastly boring affair.

Until the very end, there wasn't a moment of fear. It was not so much

a physical adventure as a spiritual one.

I had time and the privacy to spend hours thinking without having to explain

to others, without having to apologize. It was a time to sort back through

my life. I was able to remember things with a clarity and richness of

detail that's simply not possible with telephones and television sets

and traffic.

I worked my way through the memories of old loves like a gambler shuffling

through a worn and familiar deck of cards. I wept for hours over friends

lost in Vietnam and then laughed until I cried again over memories of

days and nights together with those old friends, memories that had been

lost for years in a brain overflowing with the trivialities we find so

essential to keeping our daily lives in order.

I wondered, as I have many times, what my father

would have made of this trip and wandered for hours among memories of

him, looking for clues that might help me answer that question. I still

don't know.

There were voices, of course, but they had little of importance to say.

There was a voice in the gurgling cockpit drain that sounded very much

like a TV play-by-play announcer and a nagging voice in a squeaking block

and tackle whose complaints I ignored. I heard entire conversations as

clearly as if heard through a wall, not quite clear enough to follow.

Had I expected more? A confrontation with my dark side where once and

for all I vanquished it? Was I to relive those sins in my life and find

some cathartic expiation? There were no penetrating visions and hidden

truths remain just as hidden.

But I'm a happier man. I've had my adventure. I sailed a small boat alone

across a big ocean to a small island. No one can take that away from me.

![]()

I was sure

the boat was slowly dragging its anchor closer to the rocks. I was sure

there was no way I was going to get the engine started before dark. And

finally, on my short list of things about which I was sure, I was sure

I didn't want to spend the night listening to those waves crash against

those rocks.

There seemed little choice for the heroic single-hander. I got on the

radio and called for help. And called. And called. After an hour, a Swedish

woman in uncertain English asked if I needed a tow. I said that would

be nice.

She and her husband, on their way to the next island, delayed their departure

to help. I threw them a tow line, and they stood by as I sweated to get

up the anchor, which I had thought was dragging but which now perversely

refused to give up its hold on the bottom. It took an hour, but the Swedes'

patience never flagged.

Yankee Lady was ignobly towed into harbor for all the other boats

to see, and somewhere in there is a lesson about vanity and the need for

others. I'm not sure just yet what that lesson is, but at least now I

have the time to try to figure out what it might be.

![]()

This story appeared originally Oct. 18, 1987, in West, the San Jose Mercury's Sunday magazine.