New York Times Magazine, April 12, 1970

By ROBERT HODIERNE

SAIGON

A PRIVATE first class whose company was ambushed and mauled by

the enemy will know intimately the anthill behind which he hid trying

to save his hide, but his mother in Des Moines, Iowa, will probably know

more about the whole fight than he does.

His mother may well read a wire service account in The Des Moines Register.

The Pfc. will listen to the Armed Forces Vietnam Network (A.F.V.N.) on

his radio, read his unit paper or, if he’s lucky and there’s

some extra room on the supply helicopter, read the Pacific Stars and Stripes.

If he gets Stripes he might know as much as his mother in Iowa.

The reason for this strange and somehow unfair situation is that the

papers and broadcasts that reach a G.I. are, with the exception (up

to now) of Stripes, so controlled by the military that little objective

reporting gets into them. The reader in the States who takes the time

has a chance to read something that hasn’t been muted, twisted

or mangled by the military authorities. Any muting, twisting and mangling

in the States is done by civilian reporters and editors – and

this open the door, willy-nilly, to several points of views, the Vice

President notwithstanding.

To the nearly half-million G.I.’s in Vietnam, though, there is no

escape from the military’s hand on the news. The American public

got some inkling of the Vietnam G.I.’s information lag last fall

when A.F.V.N.’s polices (i.e. that no news is the best news, and

bland news second best) were blasted on the air by one of its own commentators

(who is no longer with the network). And now the G.I.’s one relatively

good source, Stripes itself, is about to be toned down by a new editor

recently installed by the military authorities who didn’t like what

they were reading in it.

THE soldiers here are the “most” of many things. They are the most expensively equipped, trained and paid soldiers the United States has ever fielded. They are also the most literate. The graduating class of 1968, the military says, raised the education level to the highest ever. The college-educated draftee didn’t stop reading after his foul-mouthed, comic-book-scanning drill sergeant made him shave his beard and cut his hair. But when he was marched onto an airplane with a couple of hundred other G.I.’s and flown off to Vietnam, he was virtually cut off from a view of the world any broader than a career Army officer’s.

In Vietnam a G.I. can get news of the war and the world in several mostly

unsatisfactory ways. He can subscribe to papers from home – any

papers, from the most obscene, radical, left-wing underground ones

to the most right-wing. These are often weeks late, later than that

if the G.I. is with the front-line troops, who only get mail once

a week. But the Vietnam coverage of most Stateside papers, in which

the war has moved well off Page 1, does not satisfy the demand of

a G.I. in the war zone. For war news he must turn to the military

sources.

The ubiquitous A.F.V.N. – it claims its radio stations blanket

the country – popped into public attention last fall and winter

when several broadcasters accused the military of censoring the network.

It was Specialist 5 Robert Lawrence who did this on the air, much to

the surprise of nearly everyone. Lawrence is now a chaplain’s

assistant in the remote Central Highlands city of Kontum, which surprises

few.

THESE charges “shocked” and “outraged” several politicians, including Representative John Moss (D., Calif.) who heads the House Government Information Subcommittee. Moss looked into the matter in February when he was in Vietnam and concluded that there was no censorship at A.F.V.N., the same conclusion that a military investigation came to.

Moss said that the instances of alleged censorship were really only cases

of editorial judgment. He suggested that more precise guidelines need

to be laid down to insure that these judgments were at least consistent.

In fact, there is no censorship at A.F.V.N. No one man sits with a blue

pencil and a set of rules that force controversial stories off the

air. The news decisions at A.F.V.N. are made in a most haphazard way,

often by officers with little if any real news experience. The main

criterion for deciding what gets on or rather what does not get on

is one of caution

– if there is a chance, often very remote, that there will be repercussions

from a story, the individual officer on duty will kill it. When Vice

President Nguyen Cao Ky beat President Nixon to the punch in announcing

a troop withdrawal, some officer at A.F.V.N. killed the story. It is

unlikely that very many seasoned editors would have made an editorial

judgment like that.

So, while there is no censorship at A.F.V.N., while there is just overcautious,

amateurish editing, the news comes out sounding censored – and considering

the often distorted and misleading view it gives of the war, it might

just as well be censored. A.F.V.N. broadcasters do not go out to report

the war. Their war coverage consists of reading the officials news releases

– which are censored – or reading untouched wire-service copy.

Most of their newscasts are in the sterile, bookkeeper’s vocabulary

of the military. G.I.’s don’t have raging battles on A.F.V.N.;

they engage unknown-size enemy forces. They don’t blast away at

the enemy with rifles and hand grenades; they respond with organic weapons.

Aircraft don’t bomb the hell out of enemy bunkers; they hit specified

targets with selective ordnance. No cries of pain or views of grief are

conveyed by the A.F.V.N. War looks how commanders want it to look: like

a business-like operation in which decisions are coolly, professionally

made in terms of cost effectiveness. This view of war makes battle deaths

nothing more than the wiggles of a green line on a clear plastic-covered

chart in a softly lit briefing room where the most distracting noise is

the humming air conditioner.

But there’s no censorship at A.F.V.N.

UNIT newspapers, published by nearly every outfit large

enough to own a typewriter, are censored by the command. At the headquarters

of the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (M.A.C.V.) is the M.A.C.V.

Office of Information, M.A.C.O.I. It has a branch called Reviews and Analysis.

Read that “censor.” In that office a field-grade officer with

a red grease pencil and two little rubber stamps – “This item

cleared for release by M.A.C.O.I.” and “This item not cleared

for release by M.A.C.O.I.” – looks over all stories dealing

with the operational activities of units in Vietnam; that is, with the

bulk of information put out by the unit public-relations men.

These stories – that is, those that are cleared – comprise

the bulk of what goes into the newspapers financed by unit funds reserved

for the benefits of the G.I.’s. The view of the war represented

there is so foolishly slanted that most G.I.’s don’t bother

to read the papers.

All G.I.’s in Vietnam know that we use tear gas. Many of them carry

tear-gas grenades with them. If tear gas every helped anybody win a

tough battle, you’d never read about it in a unit newspapers.

The M.A.C.O.I. censor has a rule about that: “We don’t actively

publicize the use of CS [tear gas],” he writes on stories like

that. Napalm gets greased out, as do references to snipers. Stories that

talk about getting “short” – that is, stories about

G.I.’s

being happy because pretty soon they will be going home – are customarily killed. They present what the

grease-pencil warrior calls a “highly negative image of the United

States fighting man.”

The current emphasis at M.A.C.O.I. is pacification, the so-called “other

war.” There is a concerted effort to play down the fighting and

play up the loving. Unit publications and public-relations releases are

crowded with cuddly orphans, lovable nuns, sparkling new wells, big new

schools and grimacing urchins being given shots by kindly medics. It is

hard to find someone killing anyone anywhere.

The Army Reporter, a 12-pages weekly published by the United States Army,

Vietnam, an award winner that claims to be the largest Army newspaper

in the world, is pretty typical. In its March 2, issue, for example,

the front page had four stories, only one dealing with combat. The

three others were about an orphanage, new wells for a village and

a medical civic action program that was livened up by having a band

come along.

The entire second page was devoted to a summary of Army battles for the

Feb. 10-16 period. On Page 12 there was one other battle story. The rest

of the paper was devoted to features of a noncombat nature. In the week

covered by it battle stories, nearly 100 United States fighting men died

and more than 500 were wounded. There was no mention of any Unites States

Army soldiers being killed. Only one wounded soldier was mentioned. No

concept of how a fight went, who won, who lost, can be gained from a story

that gives only one side’s casualties.

The typical rationalization for this unrealistic reporting is that it

hurts the morale of the troops to see such information publicized. The

grunts, the combat troops, don’t like to see their hard fights reduced

to public-relations eyewash. If they went through hell, they want people

to know about it. But unit newspapers are in the business of making the

unit and the unit commander look good. Dead G.I.’s don’t do

that.

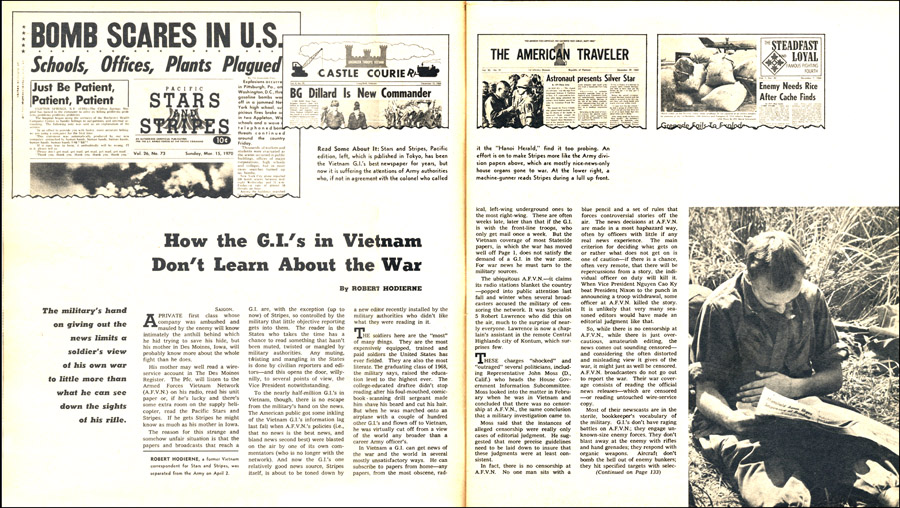

STRIPES was the one place that G.I.’s could sometimes read about the shooting, bleeding, bombing, gassing, dying and killing. A 24-page daily tabloid published in Tokyo, Stripes is a direct descendant of Willie and Joe’s World War II paper. Government-published, it is staffed by military and civilians alike. Periodically it has published some unusual stuff for a military paper. It sends reporters to the field regularly, unlike A.F.V.N. When these men come back from the front to Saigon, their stories are sent directly to Tokyo uncensored by M.A.C.O.I. No other military journalists in Vietnam can claim that privilege.

The predictable result was that many military information officers disliked

Stripes. Their job is to make their boss look good or at least to make

sure he doesn’t look bad. Sometimes Stripes did just what wasn’t

wanted. In August the paper reported that one of the Americal Division

companies fighting in the Hiepduc Valley wasn’t doing very well.

That division complained loudly and often to the then chief of information

for the Army in Vietnam, Col. James Campbell (who was slated to take over

as editor of Stripes in January). Campbell, a hot-tempered, cigar-chomping

career officer, publicly called the paper the “Hanoi Herald”

and termed one of the articles about the fighting “treasonous.”

Pretty hot stuff for the usually stodgy military. Almost at once Campbell

was fired as information chief (and his Stripes’ assignment

dropped), not because the military here disagreed with him, but because

the whole affair generated a lot of bad publicity for the military.

Remember, Campbell’s

job was to prevent bad publicity.

Campbell’s remarks were made in a speech written by him but delivered

by his deputy at an information officers’ conference in Taipei

last September. At the time Campbell said the speech was the official

view of the Army command in Vietnam, a claim that he repeated several

times. Finally, the chief of information for M.A.C.V., Col. Joseph

Cutrona, convinced Campbell on the phone that it was in his best interest

to retract the statement that he was espousing official viewpoints.

It is fairly clear, however, that the Campbell text was indeed speaking

for the Army. One of Campbell’s clerks reports hand carrying

a copy of the speech to Campbell’s general before it was delivered.

THAT wasn’t the fist time that Stripes had been under fire, however. Daily calls to the paper’s Saigon bureau about stories that just didn’t do the military any good were so common that if a day went by when one didn’t come in, the civilian bureau chief, Pat Luminello, would fret. Luminello, a veteran newsman, concluded that the military wanted a “pap sheet in which they could air their views and prevent even a hint that all was not wine and roses on the war front.”

Luminello (as a result, he says, of this statement) was relieved from

his Saigon post and reassigned to Tokyo while this article was going to

press.

In June, when the Benhet Special Forces camp was under siege, Stripes

got daily calls from M.A.C.O.I. saying stop using the word siege. When

the paper reported the road to Benhet was closed, the command insisted

it was open. The many reporters who risked the roller-coaster rides into

that outpost, on resupply helicopters that almost always drew fire but

were the only way to get to the camp, knew the road was closed. But the

M.A.C.O.I. briefing officer had to stand up in front of these men and blandly

tell them the road was open. One day the Air Force release quoted an Air

Force captain as saying the road was cut in several places. M.A.C.O.I.

still insisted it was open.

Stripes also reported that the South Vietnamese Army wasn’t doing

much to help the camp and that there weren’t any South Vietnamese troops

near the base. The reporter on the scene had watched in the command center

as the artillery officer got permission to fire into all the area surrounding

the camp, which he certainly couldn’t have got had friendly troops

been there. All of the officers at the camp were complaining, bitterly,

that there were no South Vietnamese on hand. But M.A.C.O.I. kept calling

Stripes, saying not to run this information. Stripes ran it anyway.

COL. WILLIAM V. KOCH, then a lieutenant colonel, was a persistent caller of Stripes’ Saigon office last summer. He complained a lot about word usage. He didn’t like Stripes calling Hamburger Hill Hamburger Hill. He thought it should be called Hill 971. Calling South Vietnam South Vietnam didn’t please him. He said Stripes should call it the Republic of Vietnam. North Vietnam was North Vietnam to Koch, however, and not the Democratic Republic of North Vietnam. The South Vietnamese Army should be called the Army of the Republic of Vietnam but the People’s Army of North Vietnam should be called the North Vietnamese Army. Koch also suggested that Luminello bring each night’s group of stories to M.A.C.O.I. so it could offer guidance. This was flatly refused by Stripes.

This sensitivity to certain words is what led the military to issues

its directive, “Let’s Say It Right.” That directive

prohibited calling mercenaries mercenaries. Vietcong tax collectors

became extortionists and search-and-destroy missions became search-and-clear

missions. This list also revealed the military’s often fuzzy

understanding of the enemy when it ordered that the National Liberation

Front and the People’s

Liberation Army both be called the Vietcong or North Vietnamese Army.

The file of complaints that Stripes received from the command is thick.

One repeated complaint was the Stripes reporters asked questions.

Lieut. Col Ross Johnson, now chief of information for the Army in

Vietnam, made that complaint when a Stripes reporter was looking into

racial disturbances in Camranh Bay. Lieut. Cam Stewart, an Air Force

information officer, said to a Stripes reporter that another writer

on that paper was “always

asking questions. I don’t like his attitude.”

Joseph Heller may have called it right in “Catch-22” when

he said, “Headquarters was alarmed, for there was no telling what

people might find out once they felt free to ask whatever questions

they wanted to.” Heller’s headquarters solved the problem

by making a rule that the only people who were allowed to ask questions

were those who never did. The resemblance to Vietnam is striking.

The pressure on Stripes from the military continued last summer through

the fall and into the winter. The paper so irritated the command that

it stopped inviting reporters to briefings even though Admiral John S.

McCain Jr., the commander-in-chief for Pacific forces, had ordered that

Stripes be given the same cooperation and assistance as the commercial

media.

President Nixon’s Vietnam visit provided a case in point. Everyone

guessed he was coming, but no one knew when. Luminello happened to be

in the U.S. Government’s information building in downtown Saigon

one morning when he noticed a large number of other bureau chiefs present.

When he asked what was happening, they told him they were there for the

briefing on Nixon’s upcoming visit. Luminello called Col. Gordon

Hill, then chief of M.A.C.O.I., who told Luminello, “I don’t

know anything about that, Pat. That must be an Embassy affair.”

One hour later Hill conducted the briefing on Nixon’s visit. That’s

the kind of thing that makes the Stripes people think the military in

Vietnam has it in for them.

The paper had several good things going for it during this period. The

editor was a sharp newsman, Col. Peter Sweers, who is now retired and

teaching journalism. The managing editor, John Baker, a civilian, is a

bullheaded man given to sharp displays of temper, especially when he thought

the paper was being treated poorly. Both of these men were instrumental

in making the paper a pretty honest publication.

Stripes civilian staff, which outnumbers the military editorial staff,

acts as a buffer to military pressure. These civilians are experienced

journalists recruited from the States to work in Tokyo and several other

bureaus for three-year periods. Their pay is standard Government scale,

but extra benefits such as housing allowances, military post exchange

and commissary privileges, as well as free medical care, always draw more

applications than there are openings. The Vietnam bureau chief, who bears

the brunt of the criticism, makes more than $20,000.

The paper’s military staff in Saigon was pretty good, too, during

this mid-1969-early 1970 period. It was certainly well-educated, with

degree holders from prestigious schools – Harvard, Yale, Johns Hopkins,

the University of Chicago, Berkeley, Medill at Northwestern – and

most of these reporters had professional experience before they were drafted.

For a while these reporters went on writing what they thought ought to

be written, and while lots of it got cut by the editors – mentioning

bombing Laos was then forbidden – much got printed.

But the military commanders who objected to Stripes were bound to win.

After Campbell was fired, the search for a Stripes editor to replace

Sweers began. Sweers left the paper early last fall and on Jan. 1

of this year, Colonel Koch, the man who wanted Stripes’ copy

checked by the M.A.C.O.I. people, took over. He says he is preparing

a new editorial policy for the paper. It still hasn’t become

apparent in print but the hints are everywhere. His first act was

to put the Saigon reporters back in uniform. Whereas before they had

always worn civilian clothes, they now have to wear a uniform that

immediately identifies them as enlisted men. The civilian clothes,

it was thought, helped them mingle better with civilian reporters

and made it easier for them to gather information from sources who

often have little respect for enlisted men.

An even bigger bombshell came, though, when it was learned that Koch

is planning to move the bureau out of Saigon 16 miles north to the

Army base at Longbinh. Isolated there, an hour’s drive away

through maddening traffic from the Vietnamese Government, and from

U.S. Embassy and U.S. military command sources, the bureau would be

crippled as a news-gatherer and transmitter. But this doesn’t

both Koch, who says he wants his reporters to stop concentrating on

news and do features. The move out of Saigon would certainly accomplish

that.

WITH Stripes teetering on the brink, with A.F.V.N. uncensored but uninformative and with unit publications pumping out stories of G.I.’s teaching primitive villagers how to brush their teeth, where does that leave the G.I.? No one in the military information business seems to care much. The system isn’t geared to keep the troops informed. That is not what the job of the information officers turns out to be.

Being a combat commander in Vietnam, for a career officer, is good for

that career. But it is very dangerous. Besides the chance of getting killed,

threats lurk everywhere, especially in newspapers. A Vietnam commander

has to watch his public image very carefully. Much of the public has a

great distaste for the war and hence a great distaste for people associated

with it. That’s why there aren’t very many colorful leaders

here. Col. George S. Patton III, Blood and Guts’ kid, was quoted

as saying before he left Vietnam that he liked to see Vietcong arms and

legs fly. Colorful stuff that today makes many Americans vomit. Twenty-five

or so years ago when his father was saying similar things, Americans were

smiling and saying, go get ’em George. As a result of this change,

most division combat commanders resemble henpecked bookkeepers rather

than the dashing battlefield officers of earlier wars.

Each of these self-conscious commanders has a public-relations man whose

main job is to see that nothing gets out that might tarnish that nonimage,

that might get in the way of the next promotion. Gen. Creighton Abrams

has a whole office of P.R. men who try like made to make sure no distasteful

news gets out. Since many Americans find gas warfare distasteful, the

P.R. men have a rule which prohibits the publication of news dealing with

gas warfare. Napalm and flame-throwers are ugly and make for good material

in antiwar (and hence anti-Abrams) demonstrations; the P.R. men don’t

let stories about these weapons out. Stories that detail how G.I.’s

feel about the war, honest stories that is, are also suppressed (there

is precious little flag-waving in the rice fields).

The civilian media can report most of the distasteful aspects of the war.

They are being hidden only from the G.I.’s in Vietnam. When a unit

gets in a tough fight with lots of people hurt, it comes out sounding

like a tea party in the division newspaper and on A.F.V.N.

This process of softening a harsh image might, in Washington, be called

keeping a low profile. In the military it’s called keeping your

rear down. The people who suffer the greatest lack of news as a result

aren’t the people back home but the kid who has to fight the war.

It’s bad enough to have to fight a war that you don’t understand

at all, but when you can’t even find out how the war is being fought

there is something wrong.

***

A RECENT telephone conversation in Saigon between a

reporter for Stars and Stripes and a military police officer:

REPORTER: I’m interested in statistics you have on the number of

G.I.’s smoking pot in Vietnam.

OFFICER: I can’t give you those.

REPORTER: You mean you don’t have them?

OFFICER: No, I can’t give them to you. You’ll have to talk

to the information office, M.A.C.O.I.

REPORTER: They’ll give them to me?

OFFICEER: Probably not.

REPORTER: Then why should I talk to them?

OFFICER: They’re the people in charge of not giving out information.